John Milton: Biography, Poems, Famous Works, Spouse

John Milton was born on December 9, 1608, in London. He was a poet and thinker from England. In a period of great religious flux and political turmoil, Milton wrote his epic poem Paradise Lost in 1667, which is written in blank verse and has more than ten sections. It spoke about how God drove Adam and Eve out of the Garden of Eden after they surrendered to Satan's temptation. Milton's status as one of history's greatest poets was enhanced by Paradise Lost, which is usually regarded as one of the finest works of literature ever written. He worked for the Commonwealth of England's Council of State; afterward, Oliver Cromwell was a government official.

Early Life and Education

John Milton, the son of composer John Milton and his wife Sarah Jeffrey, was born in Bread Street, London. After being abandoned by his devoted Catholic father, Richard "the Ranger" Milton, for converting to Protestantism, the senior John Milton (1562–1647) relocated to London around 1583. The older John Milton married Sarah Jeffrey (1572–1677) in London, where he also became a scrivener and achieved long-term financial success. On Bread Street, in Cheapside, near the Mermaid Tavern, he had a home where he resided and ran his business. The father of Milton had a kid who had a lifetime interest in music and made acquaintances with musicians like Henry Lawes due to his father's talents as a composer, who was well-known for his work.

Thomas Young, a Scottish Presbyterian with an MA from the University of St. Andrews, was hired as Milton's oldest son's private teacher owing to Milton's father's wealth. The poet first became aware of Christian radicalism thanks to Young. Milton continued his studies of Latin and Greek at St. Paul's School in London after Young's teaching, where the ancient languages impacted his poems and his English writing. He also wrote in Latin and Italian.

Two psalms written by Milton at the age of 15 at Long Bennington are his earliest dated works. The inconsistent compilation Brief Lives of John Aubrey, which includes first-hand accounts, is one source from the modern era. Aubrey uses a quotation from Milton's younger brother Christopher in work: When he was a kid, he put a lot of effort into his studies and stayed up late, usually until midnight or 1 a.m. He was so beautiful that they dubbed him the Lady of Christ's College due to Aubrey's further observation, "His complexion is extraordinarily fair."

Milton was admitted to Christ's College at the University of Cambridge in 1625 and earned a BA there in 1629, finishing fourth out of 24 honours graduates that year. Milton obtained his Master of Arts degree at Cambridge and was awarded it on July 3, 1632, while still training to become an Anglican priest.

A dispute between Milton and his teacher, Bishop William Chappell, may have led to his suspension in his first year at Cambridge. The first Latin elegy he ever composed, Elegia Prima, was dedicated to Charles Diodati, a friend from St. Paul's, during Lent Term 1626, proving that he was unquestionably at home in London. Chappell "whipped" Milton in response to John Aubrey's comments. Although Chappell was not a Milton fan, this story is now being called into question.

Although Chappell was unpopular with Milton, this claim is now contested. According to historian Christopher Hill, Chappell and Milton had a disagreement of opinion that could have been religious or personal. Milton also seems to have been rusticated. Milton could have been expelled from Cambridge in 1625 because of the epidemic, which profoundly influenced the city and Isaac Newton four decades later.

At Cambridge, Milton got along well with Edward King, to whom he eventually devoted "Lycidas." Theologian and dissident Anglo-American Roger Williams was another acquaintance of Milton's. Williams received Hebrew instruction from Milton in return for Dutch classes. Milton struggled with social isolation among his classmates while attending Cambridge and gaining a reputation for lyrical prowess and general intellect. He remarked that he had once seen his classmates make an effort at comedy in the college theatre and that "they felt themselves valiant men, and I thought them fools."

Milton was particularly contemptuous of the university curriculum, which featured stiff, formal arguments in Latin on obscure subjects. His sixth prolusion and the inscriptions he wrote for Thomas Hobson show that he has a sense of humour in his works. He created some of his most well-known shorter English poems. At the same time, he was a student at Cambridge, including "On the Morning of Christ's Nativity," "Epitaph on the magnificent dramatic poet, W. Shakespeare," which was his first poem to be published in print, "L'Allegro," and "Il Penseroso."

The Study, Poetry, And Travel

Milton retired to Hammersmith, where his father had moved the year before, after getting his M.A. Additionally, he conducted six years of independent private study while residing in Horton, Berkshire, starting in 1635. According to Hill, this was hardly an escape into a rural ideal because Horton was getting deforested and suffering from the plague. Hammersmith was a "suburban hamlet" at the time that encircled London, and Hammersmith had been a village before. He studied classic and contemporary works of research, literature, history, politics, religion, and philosophy to prepare for a potential career as a poet. Using notes from his Commonplace Book, which is currently housed in the British Library, one may trace Milton's intellectual growth. Milton is regarded as one of the most knowledgeable English poets due to his extensive research. Milton was fluent in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, Spanish, and Italian throughout his school and college years, in addition to his years of private study. In the 1650s, while working on his History of Britain, he also added Old English to his linguistic toolbox, and it is likely that he quickly picked up Dutch.

Even while he was still in school, Milton kept writing poetry. In 1632 and 1634, the masques Arcades and Comus, written for aristocratic clients with ties to the Egerton family, were presented. Comus defends the virtues of moderation and virginity. In honor of one of his Cambridge classmates, he donated his pastoral elegy Lycidas to a memorial fund. In Milton's poetry journal, known as the "Trinity Manuscript" since it is currently maintained at Trinity College, Cambridge, are versions of these poems that have survived. Milton set out on a 15-month journey through France and Italy in May 1638 with the assistance of a manservant. The tour ended in July or August 1639. His trips gave him new, up-close exposure to artistic and religious traditions, particularly Roman Catholicism, which complemented his academic research. He could showcase his lyrical abilities while interacting with eminent theorists and thinkers of the era. The Defensio Secunda was written by Milton and appeared to be the only source of explicit information about what took place during his "great journey." There are other documents, such as letters and references from his earlier prose tracts. However, most of the details concerning the tour came from writings that, in the words of Barbara Lewalski, "were not meant as autobiography but more as rhetoric, aiming to stress his good reputation with educated Europe."

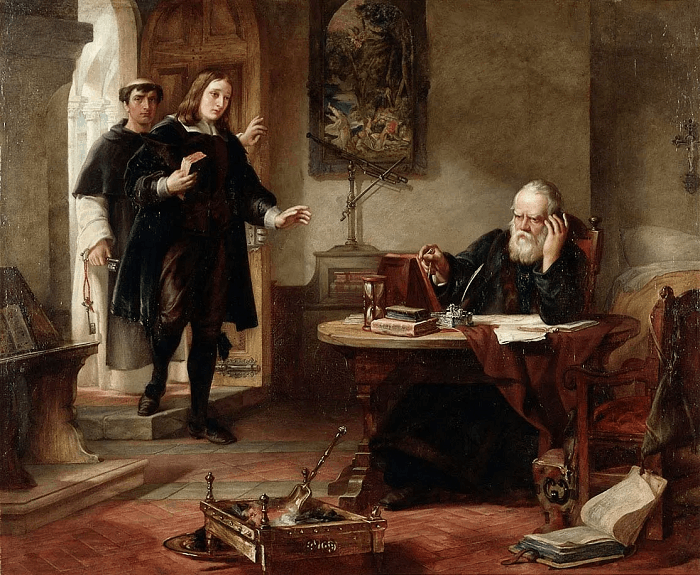

Riding a horse, he initially traveled to Calais before continuing to Paris with a message from diplomat Henry Wotton to ambassador John Scudamore. Milton was introduced to Dutch dramatist, poet, and legal philosopher Hugo Grotius by Scudamore. Soon after the meeting, Milton departed from France. He moved southward from Nice to Genoa, Livorno, and Pisa. Milton got there in July 1638 at Florence. Milton took in many of the city's sights and buildings while there. He made acquaintances in Florentine intellectual circles thanks to his straightforward personality and knowledge of neo-Latin poetry. He also had the opportunity to meet Galileo, who was living under house arrest in Arcetri. Milton undoubtedly paid visits to many local institutions, including Apatisti and Svogliati, the Florentine Academy, and the Accademia Della Crusca.

In September, he moved on to Rome and left Florence. Milton had easy access to Rome's intellectual community because of the relationships he made in Florence. People like Giovanni Salzilli were amazed by his lyrical ability and commended Milton in an epigram. Milton met English Catholics who were guests at the supper, including theologian Henry Holden and poet Patrick Cary, despite his distaste for the Society of Jesus. Oratorios, operas, and melodramas were among the other musical performances he attended. Due to the Spanish occupation, Milton arrived in Naples near the end of November but only lasted for one month. At that time, he met Giovanni Battista Manso, who supported Giambattista Marino and Torquato Tasso.

Milton originally intended to depart Naples for Sicily and then go to Greece. Still, he changed his plans and returned to England in the summer of 1639 due to what he described in Defensio Secunda as "sad tidings of civil war in England." When Milton learned of the passing of his high school buddy Diodati, things grew more difficult. In reality, Milton remained on the continent for seven months, spending time in Geneva with Diodati's uncle before returning to Rome. Milton said in Defensio Secunda that he had received warnings not to return to Rome because of his sincerity towards religion. Still, he spent two months there, attended Carnival, and met Lukas Holste, a Vatican librarian who showed Milton through the library's collection. Milton was invited to an opera performance sponsored by Cardinal Francesco Barberini after being introduced to him. Milton left for Florence once more in March, spending two months there while continuing to attend academy sessions and visiting friends. Lucca, Bologna, and Ferrara were all stops on his route from Florence to Venice. The Republicanism paradigm Milton encountered in Venice would eventually play a significant role in his political works, but he quickly discovered a different model while visiting Geneva. In either July or August of 1639, Milton set off from Switzerland and went through Paris and Calais before eventually returning to England.

Civil War, Prose Tracts, And Marriage

Milton started writing prose pamphlets against the episcopacy in support of the Puritan and Parliamentary causes after returning to the UK, where the Bishops' Wars foreshadowed future violent conflict. Milton's first attempt at polemics was Of Reformation Affecting Church Discipline in England (1641), which was followed by Of Prelatical Episcopacy, the two defenses of Smectymnuus (a group of Presbyterian divines called after their initials; the "TY" belonged to Milton's old teacher Thomas Young), and The Reason of Church-Government Urged Against Prelaty. With several bursts of genuine eloquence, illuminating the gruff, divisive idiom of the day and drawing on his extensive knowledge of church history, he fiercely assailed the High Church faction of the Church of England and its leader, William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Milton, funded by his father's finances, started teaching privately at this point, instructing his nephews and other wealthy kids. In 1644, after having conversations with Samuel Hartlib, an advocate of educational reform, and as a result of this experience, he wrote the brief essay On Education, which called for the reformation of the national colleges.

When Milton visited the manor home at Forest Hill, Oxfordshire, in June 1642, he married Mary Powell when she was 17. Mary's inability to fit in with Milton's frugal lifestyle or get along with his nephews caused the marriage to start poorly. Milton disapproved of her royalist ideals and thought her to be mentally unappealing. It's also believed that she resisted having the marriage consummated. Mary quickly returned to stay with her parents and did not return until 1645, in part due to the start of the Civil War.

Milton wrote several pamphlets over the following three years in response to her departure, advocating for the morality and legitimacy of divorce on grounds other than infidelity. (Anna Beer, one of Milton's more recent biographers, cites an absence of supporting material and the risks of cynicism in arguing that it was not always true that the private life so fueled the public polemicizing.) Milton and Hezekiah Woodward, who experienced greater difficulty, both had run-ins with the law in 1643 over these publications

Milton was inspired to compose Areopagitica: A Speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenced Printing to the Parliament of England, his famous attack on pre-printing censorship, by the negative reception given to the divorce booklets. Milton starts to combine the ideals of Christian liberty with neo-Roman liberty in Areopagitica, where he also joins the parliamentary struggle. During this period, Milton courted a different woman, Davis, who, according to what is known about her, declined his advances. That Mary Powell abruptly begged him to take her back was enough to persuade her to come back to him, though, and that was enough. He had two kids quickly after their reconnection.

Secretary For Foreign Tongues

Milton used his pen to support the republican values upheld by the Commonwealth after the Civil War, which was won by the parliamentary side. Milton was appointed Secretary for Foreign Tongues by the Council of State in March 1649 due to his political standing. The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (1649) asserted the power of the people to keep their rulers accountable and indirectly approved regicide. His primary responsibility was to write the Latin and other languages used in the English Republic's foreign letters. Still, he was also required to provide propaganda for the government and act as a censor.

He responded to the Eikon Basilike, a fantastic best-seller widely believed to have been written by Charles I and portraying the King as an honest Christian victim, by publishing Eikonoklastes, an unambiguous defense of the regicide, in October 1649. The monarchy's defense, Defensio Regia pro-Carolo Primo, was authored by eminent humanist Claudius Salmasius and released by exiled Charles II and his followers a month later. The Council of State gave Milton till January of the next year to gather the support of the English people. Given the European public and the English Republic's goal to achieve diplomatic and cultural legitimacy, Milton labored more carefully than usual as he relied on the knowledge accumulated by his years of research to create a comeback.

Milton's Latin defense of the English people, sometimes referred to as the First Defence, was released on February 24, 1652. The First Defence saw multiple editions, and Milton's flawless Latin language swiftly established his name across Europe. Despite not being published until 1654, he began his Sonnet 16 with the phrase "Cromwell, our head of men" and addressed it to "The Lord Generall Cromwell in May 1652."

Milton wrote the second defense of the English people, known as Defensio Secunda, in 1654 in reaction to the anonymous Royalist book "Regii Sanguinis Clamor ad Coelum Adversus Parricidas Anglicanos" [The Cry of the Royal Blood to Heaven Against the English Parricides], which made several direct personal assaults on Milton. The second defense lauded and urged the now-Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell to uphold the Revolution's founding ideals. In reaction to an assault on him by Alexander Morus, whom Milton mistakenly claimed wrote the Clamor (actually written by Peter du Moulin), Milton penned the autobiographical Defensio pro se in 1655. Until 1660, Milton served as the Commonwealth Council of States' Secretary for Foreign Tongues, albeit after becoming completely blind; Andrew Marvell and Georg Rudolph Wecklein, as well as Philip Meadows, took up the majority of the job after Milton's appointment.

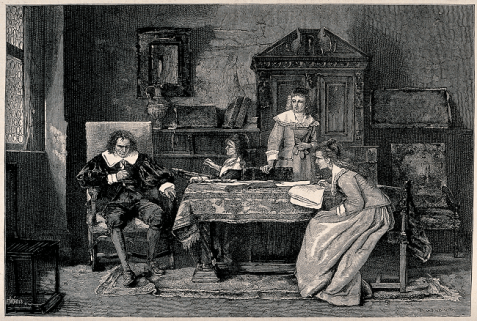

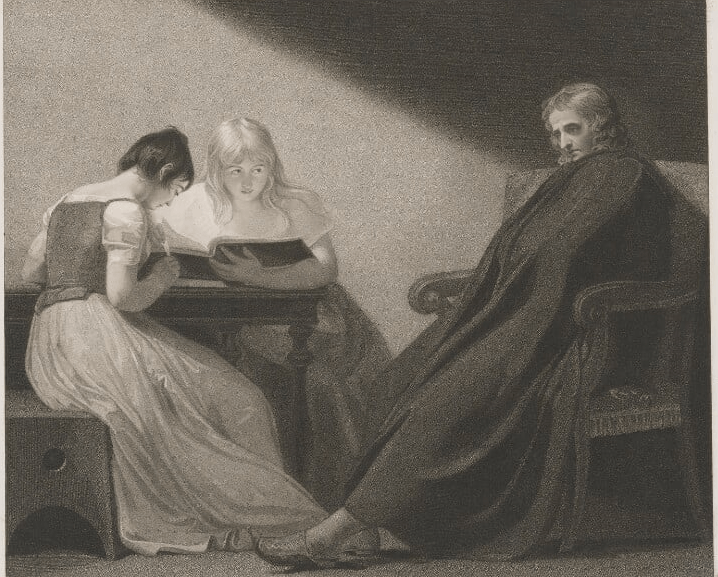

Milton lost his sight by 1652; the exact origin of his blindness is unknown, although bilateral retinal detachment or glaucoma are the most plausible candidates. Due to his poor eyesight, amanuenses like Andrew Marvell had to copy down the rhymes and writing he had dictated to them. It is assumed that this was when he wrote one of his most well-known stanzas, "When I Consider How My Light is Spent," which subsequent editor John Newton renamed "On His Blindness."

The Restoration

The English Republic broke apart into the rival military and political groups after Cromwell's death in 1658. Conversely, Milton, on the other hand, stubbornly held to the ideas that had initially motivated him to write for the Commonwealth. A Treatise of Civil Power, which attacked the idea of a state-dominated church (a viewpoint known as Erastianism), and Considerations affecting the likeliest ways to remove hirelings, criticized corrupt practices in church government, were both published in 1659. Despite the will of the people, the military, and the parliament, Milton produced several suggestions to maintain a non-monarchical administration as the Republic fell apart.

Milton fled into hiding after the Restoration in May 1660 out of concern for his life, and his works were burned along with a notice for his arrest. He reappeared when he gave a general amnesty, but not before being detained for a short time by authorities, thanks to the intervention of powerful friends like Marvell, who is now an MP. On February 24, 1663, Milton tied the knot thrice. This time, he married 24-year-old Wistaston, Cheshire native Elizabeth (Betty) Minshull. Lone leaving his only surviving residence, Milton's Cottage in Chalfont St. Giles, during the Great Plague did, he spend the final ten years of his life living peacefully in London.

During that time, Milton released several unimportant literary works, including the grammar manual Art of Logic and History of Britain. Of True Religion (1672), which argued for tolerance (except Catholics), and a version of a Polish tract for an elective monarchy was the only clearly political writings he ever produced. When James, Duke of York, the presumed successor to the English throne, was being tried for exclusion from the throne because he was a Roman Catholic, he mentioned both books in the exclusion argument. Politics were obsessed with this issue throughout the 1670s and 1680s, which led to the Whig Party's establishment and the Glorious Revolution.

Death

Milton passed away on November 8, 1674. He was laid to rest in London's St. Giles-without-Cripplegate Church on Fore Street. The cause of death, however, was either gout or intoxication, according to several reports. He had "his erudite and wonderful friends in London, not without a kindly concourse of the vulgar," according to an early biographer who attended his cremation. In 1793, a memorial by John Bacon, the Elder, was erected.

Family

Anne, Mary, John, and Deborah were the four children born to Milton and his first wife, Mary Powell.

The problems that followed Deborah's delivery claimed Mary Powell's life on May 5, 1652. Milton had daughters who lived to adulthood, but their connection was never easy.

In Westminster's St. Margaret's Church on November 12, 1656, Milton wed Katherine Woodcock. The third marriage of Milton with Elizabeth Mynshull took place on February 24, 1663. He married Elizabeth Mynshull, or Minshull (1638–1728), a rich pharmacist and philanthropist in Manchester who was the niece of Thomas Mynshull. The wedding was held at St. Mary Aldermary in the City of London. John Aubrey said the couple's marriage appeared joyful despite their 31-year age difference and lasted for more than 12 years until Milton's passing. Elizabeth was Milton's "third and best wife," according to a sign on the wall of Mynshull's House in Manchester. Although Milton's cousin Edward Phillips believes that Mynshul "mistreated his children throughout his life and deceived them at his funeral," Samuel Johnson asserts that Mynshul was "a domestic companion and attendant."

Edward and John Phillips, his nephews and the sons of Milton's sister Anne, received education from Milton and became authors. Edward was the first biographer of Milton, while John served as his secretary.

Poetry

Milton's poetry took a while to gain popularity, at least in his name. In 1632, the Second Folio edition of William Shakespeare's works featured "On Shakespeare," his first poem to be published, under an anonymous name. There have been rumors that Milton wrote marginal comments in a copy of the First Folio that has been marked. In the enthusiasm around the potential for establishing a new English government, Milton gathered his work in 1645 and published Poems. Comus was released in 1637 under anonymous authorship, and Lycidas appeared in 1638 with a J. M. Otherwise signature in Justa Edouardo King Naufrago. Before Paradise Lost debuted in print in 1667, only a compilation of his poems from 1645 had been published.

Paradise Lost

The blind and poor Milton wrote his masterpiece, the blank-verse epic poem Paradise Lost, between 1658 and 1664 (first edition), with minor but substantial changes appearing in 1674 (second edition). Milton was a blind poet who used several assistants to whom he dictated his lyrics. According to others, the poem expresses his sadness over the Revolution's failure while reaffirming a deep hope in human potential. According to certain literary critics, Milton's steadfast devotion to the "good old cause" is frequently alluded to throughout his works.

Paradise Lost publishing rights were sold by Milton to publisher Samuel Simmons on April 27, 1667, for £5 (about £770 in 2015 buying power), with an additional £5 due if and when each print run of 1,300–1,500 copies sold out. Published in August 1667, the original print run of the quarto edition cost three shillings per copy (about £23 in 2015 buying power equivalent) and was consumed within eighteen months.

After publishing Paradise Lost, Milton followed it up with Paradise Regained, released in 1671, and the drama Samson Agonistes. Milton's post-Restoration political environment is also reflected in both of these works. Before oversaw Milton's second edition of Paradise Lost, he passed away in 1674. It included prefatory lines by Andrew Marvell and a description of "why the poem does not rhyme." Milton reprinted his 1645 poems in 1673 with a collection of his letters, Latin prolusions, and other writings from his Cambridge days.

Views

De Doctrina Christiana, an incomplete religious manifesto said to have been composed by Milton and outlining many of his unorthodox theological beliefs, was found and released in 1823. Milton's core convictions were eccentric, not shared by any one party or sect, and frequently went beyond the prevailing orthodoxy of the period. The Puritans' stress on the importance and inviolability of conscience set the tone for their tone. Henry Robinson, in Areopagitica, foresaw him even though he was unique.

Philosophy

Although Milton's ideas are typically seen as being compatible with Protestant Christianity, Stephen Fallon claims that by the late 1650s, Milton may have at least experimented with the idea of monism or animist materialism, the theory that everything in the universe—from stones and trees to bodies to minds, souls, and even God—is made up of a single material entity that is "animate, self-active, and free." According to Fallon, Milton developed this viewpoint to reject the Hobbesian mechanical determinism and the mind-body dualism of Plato and Descartes. Fallon claims that Milton's monism is most prominently displayed in Paradise Lost, where he depicts angels eating and appearing to engage in sexual activity, and in De Doctrina, where he rejects the idea that people have two distinct natures and supports the Creation ex Deo argument.

Political Thought

Milton was a poet who was "passionately independent, Christian, and humanist." He is shown in English Puritanism from the seventeenth century when the world was said to have "turned upside down." He was a Puritan, yet he wouldn't give up his morals to support political party ideas on matters of public policy. Thus, Milton's political philosophy produced perplexing results due to conflicting beliefs, a reformed religion, and a humanist mentality.

A theological debate over the issue of the divine rights of monarchs gave rise to Milton's seemingly conflicting position on important issues of the day. He appears in charge in both situations as he assesses the predicament brought on by the division of English society along religious and political lines. He helped the Puritans win the day by fighting alongside them in opposition to the King's party, the Cavaliers. However, when attempts were made to restrict free expression in that same democratic and constitutional system, Milton responded with Areopagitica out of his humanistic fervor.

In November 1644, Areopagitica was composed in reaction to the Licensing Order.

The most effective way to categorize Milton's politics is by following his life's relevant eras by following the relevant eras of his life. Church politics and the opposition to the episcopacy were the main discussion topics from 1641 to 1642. He wrote in 1649–1654 in the wake of Charles I's execution and argumentative support of the murder and the prevailing Parliamentarian system, following his divorce essays, Areopagitica and a gap. He then predicted the Restoration and wrote to prevent it in 1659–1660.

Particularly his dedication to republicanism, Milton's convictions were occasionally controversial. Milton would be hailed as the founding father of liberalism in subsequent decades. According to James Tully, republican and contractionary notions of political freedom unite with Locke and Milton in contrast to the inactive and disengaged submission put forth by absolutists like Hobbes and Robert Filmer.

Marchamont Nedham was a companion and comrade in the pamphlet battles. Austin Woolrych believes that despite their proximity, their ideologies do not share much in common outside of a general Republican outlook. According to Blair Worden, Nedham and Milton would have believed that the Rump Parliament's issue was not the republic itself but rather the reality that it was not a true republic, along with others like Andrew Marvell and James Harrington.

Theology

Despite not being a theologian or a priest, he developed John Milton's finest ideas on a foundation of theology, notably English Calvinism. In the face of the religious revolutions of his day, John Milton struggled with important Christian teachings. The great poet was unquestionably a Reformed person (though his grandfather, Richard "the Ranger" Milton, had been Roman Catholic). However, generous-hearted humanism was required for Milton's Calvinism to take form. Like many Renaissance painters before, Milton tried to combine Christian doctrine with classical forms. In his early works, the poet narrator portrays the conflict between immorality and virtue, which is constantly linked to Protestantism. By placing ideals of virtue and purity above the customs of court merriment and superstition in Comus, Milton may employ the Caroline court masque in a satirical manner. Milton's theological themes are increasingly pronounced in his later works.

Harris Fletcher, writing at the start of the development of the study of the use of scripture in Milton's work (poetry and prose, in all the languages Milton learned), observes that Milton frequently clipped and altered biblical passages to fit the purpose, offering specific chapters and verses only in his writings for a more specialized reading. Regarding Milton's abundance of Scripture quotes used by Milton, Fletcher writes, "For this book, I have collected roughly 25,300 of the five to ten thousand direct Biblical quotations that appear there." The Authorized King James Version was the traditional English Bible used by Milton. He frequently used Immanuel Tremellius' Latin translation when referring to and writing in other languages, even though "he was equipped to study the Bible in Latin, in Greek, and Hebrew, including the Targumim or Aramaic paraphrases of the Old Testament and the Syriac version of the New Testament, combined with the extant commentaries of those different editions."

Milton espoused numerous orthodox and heterodox Christian theological stances. The Racovian Catechism, based on a non-trinitarian doctrine, was authorized for publication by William Dugard in August 1650. He has been accused of denying the Trinity, thinking instead that the Son was subservient to the Father, a view known as Arianism; his sympathy or interest was undoubtedly aroused by Socinianism.

Much of Milton's theology, including what is purported to be his Arianism, is still up for discussion. In his final writings, he states that "the teaching of the Trinity is a plain truth in Scripture," refuting Rufus Wilmot Griswold's claim that there is a line in any of his major works from which can conclude that he was an Artist. Milton labeled the Socinians and Arians as "schismatics" and "errorists," with Arminians and Anabaptists in Areopagitica. Although he wasn't always easy to place in a more specific religious group, a source described him as generically Protestant. John Rogers said in 2019 that Isaac Newton and John Milton were both heretics who were Arians, as most scholars today concur.

Milton showed his disdain for Catholicism and the episcopacy in his 1641 dissertation, "Of Reformation," in which he compared Rome to modern-day Babylon and compared bishops to Egyptian taskmasters. Milton's puritanical fondness for Old Testament imagery is seen in the similarities. He was familiar with the works of John Calvin, Paulus Fagius, David Pareus, and Andreus Rivetus, who each wrote a commentary on Genesis.

Through Interregnum, Milton frequently depicts England, freed from the shackles of worldly monarchy, as an elect country similar to Old Testament Israel. Oliver Cromwell is portrayed as a modern-day Moses. These ideas were intertwined with Protestant ideas about the Millennium, which certain groups, like the Fifth Monarchists, believed would come to England. Milton, however, eventually articulated orthodox views on the prophecy of the Four Empires and critiqued the "worldly" millenarian beliefs of these and others.

The Stuart monarchy's restoration in 1660 marked the start of a new period in Milton's career. Milton laments the demise of the holy Commonwealth in his works Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained, and Samson Agonistes. Milton's may allegorically reflect a depiction of England's recent fall from grace in the Garden of Eden. At the same time, Samson's blindness and captivity—which resemble Milton's loss of sight—may symbolize England's heedless acceptance of Charles II as king. The idea that a person's soul remains dormant after death is known as mortals, and Paradise Lost illustrates it.

Milton maintained his spiritual belief despite the Restoration of the Monarchy; Samson demonstrates how the loss of national redemption need not exclude personal salvation, and Paradise Regained demonstrates Milton's ongoing trust in the hope of Christian salvation through Jesus Christ.

The Dictionary of National Biography described how he had been detached from the Church of England by Archbishop William Laud. Then it moved likewise from the Dissenters by their criticism of religious tolerance in England. Despite the failures experienced by his cause, he nonetheless upheld his faith.

Religious Toleration

Milton argued in the Areopagitica that the contending Protestant denominations should have "the liberty to know, to express, and to debate freely according to conscience, above all liberties." William Hunter, an American historian, claims, "Milton promoted abolishment as the sole practical strategy for obtaining widespread acceptance." "Government should acknowledge the gospel's influence rather than trying to compel a man's conscience."

Legacy And Influence

After publishing Paradise Lost, Milton's status as an epic poet became apparent. He significantly impacted English poetry in the 18th and 19th centuries, and he was frequently regarded as being on par with or even better than Shakespeare and other English poets. The regicide Edmund Ludlow stated Milton was an early Whig. At the same time, the High Tory Anglican preacher Luke Milbourne grouped him with other "Agents of Darkness," including John Knox, George Buchanan, Richard Baxter, Algernon Sidney, and John Locke. However, Milton was promoted by Whigs from the beginning and denounced by the Tories. The Radical Whigs, whose philosophy was crucial to the American Revolution, were greatly affected by the political views of Milton, Locke, Sidney, and James Harrington. Miltonists are contemporary academics who study Milton's life, politics, and work: "His work has been the focus of a great deal of academic investigation."

The London churchyard of St. Mary-le-Bow is accessible by the John Milton Passage, which was inaugurated in 2008.

Early Reception of The Poetry

Early supporter John Dryden started the practice of referring to Milton as the poet of the sublime in 1677. The State of Innocence and the Fall of Man: An Opera by Dryden, published in 1677, provides proof of an instantaneous cultural effect. Patrick Hume served as the first editor of Paradise Lost beginning in 1695. He provided comprehensive equipment for annotation and analysis, focusing especially on looking for references.

A modified version of Paradise Lost was presented in 1732 by the classical scholar Richard Bentley. Zachary Pearce assaulted Bentley the next year because he thought he was being arrogant. According to Christopher Ricks, Bentley was "incorrigibly eccentric" and "acutely wrong-headed" in his capacity as a critic was "incorrigibly eccentric" and "acutely wrong-headed" in his capacity. William Empson believes Pearce has shown too much sympathy for Bentley's fundamental point of view.

Theodore Haak authored a preliminary, incomplete version of Paradise Lost in German, and Ernest Gottlieb von Berge built on it to produce a standard verse version. Johann Jakob Bodmer's later successful literary adaptation greatly impacted Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock. Henry Fuseli, an artist, brought the German-language Milton tradition back to England.

Milton's poetry and non-poetic writings were highly regarded and discussed by a number of 18th-century Enlightenment intellectuals. These individuals included John Dryden, Alexander Pope, Joseph Addison, Thomas Newton, and Samuel Johnson. An extensive set of comments, annotations, and analyses of certain Paradise Lost sections, for instance, were written by Joseph Addison in The Spectator. Jonathan Richardson Senior and Jonathan Richardson Junior co-wrote a book of criticism.

An extended version of Milton's poetical works with comments by Thomas Newton, Dryden, Pope, Addison, and the Richardsons (father and son) was released in 1749. Early Enlightenment intellectuals honored Milton, and Newton's edition of Milton represented the apex of that honor. Richard Bentley's famous version, previously discussed, may also have inspired me. Milton was mentioned in Samuel Johnson's Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets, which also contained his comments on Paradise Lost (1779–1781). Voltaire's statement in The Age of Louis XIV states, "Milton remains the glory and wonder (admiration) of England."

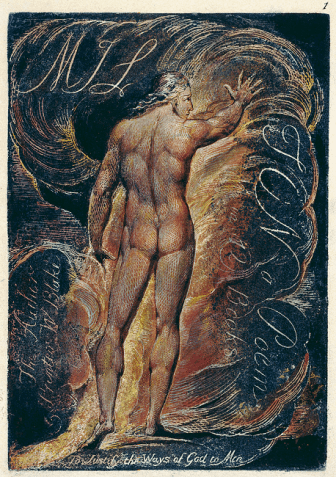

Blake

William Blake regarded Milton as a significant English poet. Blake regarded himself as the poetical child of Milton and recognized Edmund Spenser as his forerunner. Blake incorporates Milton as a character in Milton: A Poem in Two Books.

Romantic Theory

Edmund Burke supported the theory of the magnificent, and he saw Milton's portrayal of hell as a great example of the sublime as an artistic idea. Burke anticipated seeing it among mountain peaks, a storm at sea, and infinity. In The Beautiful and the Sublime, he stated that "Milton appears better to have known the mystery of intensifying, or of placing awful things, if I may use the term, in their sharpest light, by the force of a prudent obscurity."

However, most Romantic writers disapproved of his devotion and admired his study of blank poetry. William Wordsworth based The Prelude, his blank verse epic, on Paradise Lost and opened his sonnet "London, 1802," with the line "Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour." The Miltonic poem can only be written in an artistic or, more precisely, artist's humor, according to John Keats, who felt the yoke of Milton's look to be unwelcoming. Even though Keats thought Paradise Lost was a "wonderful and vast curiosity," the author found his epic poem Hyperion unsatisfying due to its overuse of "Miltonic inversions," among other reasons. Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar observe that many critics believe Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein to be "one of the primary 'Romantic' interpretations of Paradise Lost" in their book The Madwoman in the Attic.

Later Legacy

Milton's impact persisted into the Victorian era, with George Eliot and Thomas Hardy notably influenced by his poetry and life. The hostile criticism of T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound in the 20th century did not diminish Milton's prominence. In response to Eliot's remarks, particularly the assertion that "the study of Milton could be of no help: it was only a hindrance," F. R. Leavis said in The Common Pursuit, "As if it were a question of choosing not to study Milton! The issue was more with getting away from an effect that was so hard to get away from since it was unacknowledged and belonged to the environment of the routine and "natural." Milton is the key issue with any theory and history of poetic impact in English, according to Harold Bloom's The Anxiety of Influence.

Even today, the First Amendment of the US Constitution is invoked about Milton's Areopagitica. Many public libraries, like the New York Public Library, have a quote from Areopagitica on display. It reads, "A good book is the priceless lifeblood of a master soul, embalmed and treasured up on purpose for a life beyond life."

The phrase "His dark materials to make other worlds" appears in Paradise Lost's Book II, line 915, and serves as the basis for Philip Pullman's trilogy His Dark Materials. Milton is referred to as "our greatest public poet" by Pullman, who was anxious to create a young adult-friendly rendition of the poet's work.

In T. S. Eliot's opinion, no other poet makes it so impossible to evaluate the poem for what it is—poetry—without our religious and political predispositions making an unauthorized admission.

Literary Legacy

Later poets were affected by Milton's use of blank poetry and other stylistic developments (such as rhetorical voice and vision, unusual diction, and phraseology). Paradise Lost was cited as a particular example of poetic blank verse at the time, which was seen to be separate from its usage in verse theater. "Mr. Milton is acknowledged as the parent and originator of blank verse among us," declared Isaac Watts in 1734. For a century, the term "Miltonic verse" may have been used to refer to blank verse as poetry, a new literary form distinct from the drama and the heroic couplet.

The notion of regular rhythm had already become ingrained in English culture before Milton, to the point that it was almost part of their character. Samuel Johnson stated that the "Heroick measure" is "pure" when the focus is on every second word throughout the entire line. The recurrence of this sound or percussion at equal intervals is the most harmonious a single verse can be. Most people thought the center and end of the line were ideal for caesural breaks. Lines were frequently octosyllabic or deca-syllabic and lacked enjambed ends to sustain this symmetry. Milton added adjustments to this structure, such as a trisyllabic foot, inverted or mildly stressed stresses, and pauses that were moved to all points of the line. According to Milton, these characteristics show "the transcendental unity of order and freedom." The English had been writing distinct lines for so long that they could not break the practice, even among admirers who were reluctant to embrace such deviations from conventional metrical systems. According to Scott of Amwell, Henry Pemberton, Oliver Goldsmith, and Isaac Watts, Milton's frequent deletion of the first unaccented foot was "displeasing to a nice ear." These authors also desired their lines to stand out from one another. It wasn't until the latter half of the 18th century that poets, starting with Gray, started to see the value of "the construction of Milton's harmony... how he loved to change his pauses, measures, and feet, which gives his versification that delightful air of freedom and wildness." The American poet and reviewer John Hollander would go so far as to claim that Milton "was able, by manipulating that most amazing instrument of English meter... to develop a new way of image-making in English poetry" by the turn of the 20th century.

Milton's quest for freedom permeated even his terminology. It had several Latinized neologisms in addition to terms that had long since lost favor and whose meanings had become obscure. Francis Peck recognized a few instances of Milton's "old" terms in 1740. Later poets adopted the so-called "Miltonian dialect," with Pope using Paradise Lost's language in his Homer version and Gray and Collins' lyric poetry regularly criticized for using "obsolete terms out of Spenser and Milton." The Seasons, The Castle of Indolence, and other of Thomson's best poems (which share the same tone and sensibility as Paradise Lost) were written in language purposefully modeled after Miltonian vernacular. English poetry showed a gradually growing focus on the symbolism, creative, and lyrical worth of words after Milton, from Pope to John Keats.

Musical Settings

Hubert Parry (1848–1918) arranged Milton's poem On the Morning of Christ's Nativity as a huge choral piece, while Cyril Rootham arranged At a solemn Musick for choir and orchestra as Blest Pair of Sirens (1875–1938). As a versed version of Psalm 136, Milton also composed the hymn Let us with a gladsome spirit. Handel did a fantastic job of setting "L'Allegro" and "Il Penseroso," which included new material (1740).